"News From Nowhere" - An 1890 Novel Revisited

Written in 1890 by William Morris "News from Nowhere" is a compelling formulation of his views on art, work, community, family, and the nature and structure of the ideal society. One might say it's a Utopian narrative or something like science fiction, but without question, it is an immensely entertaining novel. And one that has cause for resonance today.

You can read the work yourself here at no cost.

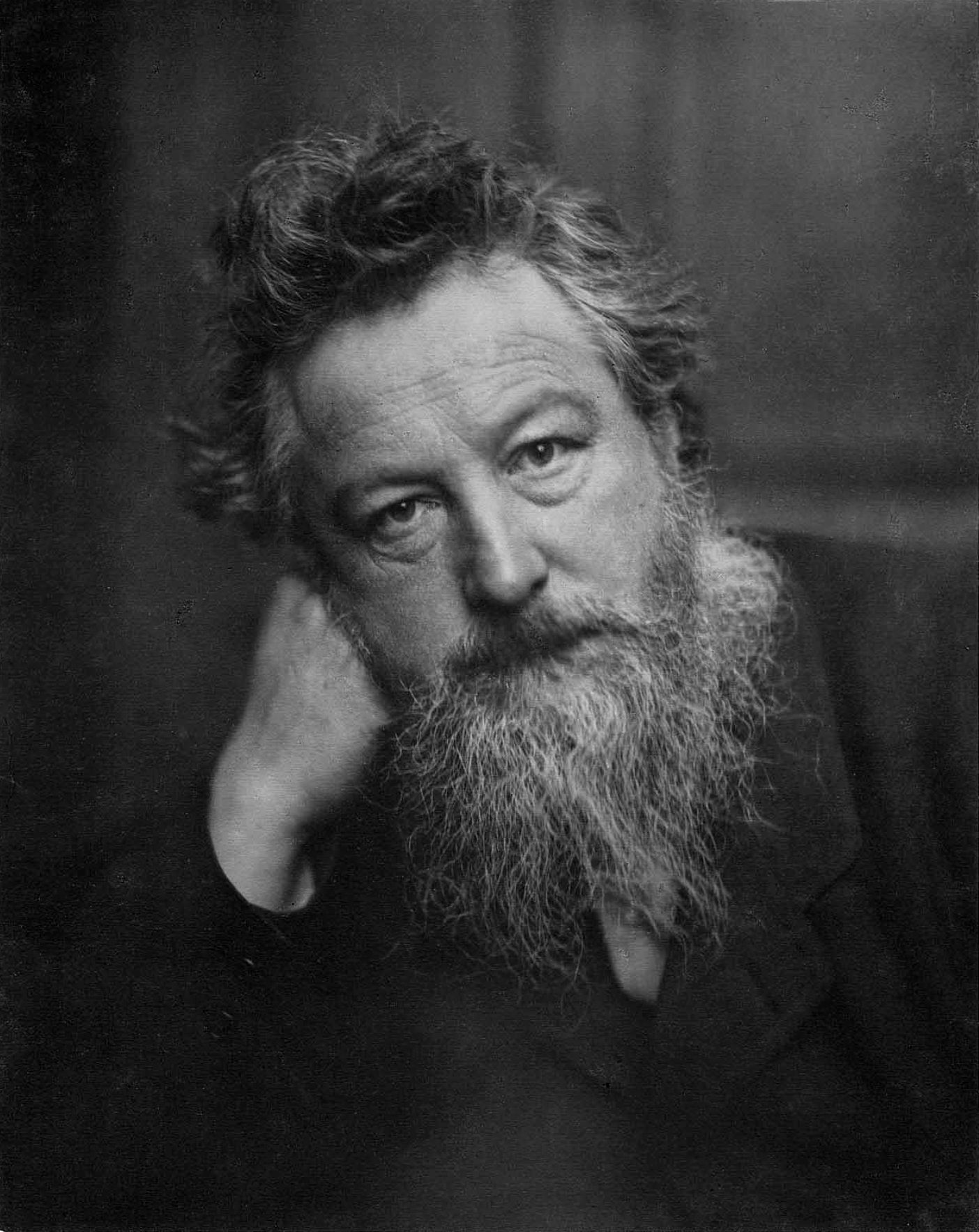

William Morris (1834-1896) is probably best-known today as a Victorian designer whose work has never gone out of fashion. You can buy Morris merchandise – from coasters to picture frames to ties to mugs – in the gift shops of every big design museum. Do an internet search of his name, and your screen will fill up with cascades of dense, colorful ornaments.

But Morris was also a radical thinker, and his novel "News from Nowhere" (1890), has striking applications in the internet era.

In "News from Nowhere", Morris imagined a world in which human happiness and economic activity coincided. He reminds us that there needs to be a point to labor. That "making ends meet" was simply not enough. Our labors create happiness for all – consumer and creator; and this differs with what we've come to understand as capitalism in the modern world which is more or less a meaningless treadmill where the point of most human endeavors is lost.

Acceptance of human endeavor as meaningless activity outside of making ends meet forces one into a horrible life, one which leads nowhere but the grave.

In Morris’s society, there is no monetary system.

In 2090 ‘wage slavery’ is obsolete, and parliamentary democracy has given way to new forms of cooperation that eliminate the need for government as we know it.

The means of production are democratically controlled, and people derive pleasure in sharing their interests, goals and resources.

When News from Nowhere was first published, it featured the trappings of a classic utopia, including that it appeared to be unattainable. Yet today we have very different technological potentials.

Commons-based production need not be a pipe dream. The ‘commons’ is a social system that refers to resources managed and shared according to the rules and the norms defined by the productive community. It is an old idea that was not lost with the European land enclosures of the 16th century. Today however, successful commons are produced routinely.

The danger, were such a path to be fully co-opted by the current (very) dominant context, is obvious, and it must realistically be acknowledged. If you profit from an economic model on a large scale, if you draw your rents from it, why would you not fight for it, even when this is not good for anyone else? The counterculture is not only here, it is gaining ground, so far.

Morris envisioned a future in which humans would be free to create

and to ‘delight in the life of the world’. This is no longer far fetched.

Most menial labor that people are not fond of doing could be done by machines.

The maintenance of infrastructure can be shared.

People will be free to work at whatever task gives them pleasure.

It's a real possibility. And it's within grasp.

You can read the work yourself here at no cost.

William Morris (1834-1896) is probably best-known today as a Victorian designer whose work has never gone out of fashion. You can buy Morris merchandise – from coasters to picture frames to ties to mugs – in the gift shops of every big design museum. Do an internet search of his name, and your screen will fill up with cascades of dense, colorful ornaments.

But Morris was also a radical thinker, and his novel "News from Nowhere" (1890), has striking applications in the internet era.

In "News from Nowhere", Morris imagined a world in which human happiness and economic activity coincided. He reminds us that there needs to be a point to labor. That "making ends meet" was simply not enough. Our labors create happiness for all – consumer and creator; and this differs with what we've come to understand as capitalism in the modern world which is more or less a meaningless treadmill where the point of most human endeavors is lost.

Acceptance of human endeavor as meaningless activity outside of making ends meet forces one into a horrible life, one which leads nowhere but the grave.

In Morris’s society, there is no monetary system.

In 2090 ‘wage slavery’ is obsolete, and parliamentary democracy has given way to new forms of cooperation that eliminate the need for government as we know it.

The means of production are democratically controlled, and people derive pleasure in sharing their interests, goals and resources.

When News from Nowhere was first published, it featured the trappings of a classic utopia, including that it appeared to be unattainable. Yet today we have very different technological potentials.

Commons-based production need not be a pipe dream. The ‘commons’ is a social system that refers to resources managed and shared according to the rules and the norms defined by the productive community. It is an old idea that was not lost with the European land enclosures of the 16th century. Today however, successful commons are produced routinely.

Wikis for instance are commons.

Are we seeing the beginnings of a world catching up with Morris's vision?

Maybe.

As recently as two decades ago, most people would have thought it absurd to countenance a free and open encyclopedia, produced by a community of dispersed enthusiasts primarily driven by other motives than profit-maximization, and the idea that this might displace the corporate-organised Encyclopedia Britannica and Microsoft Encarta would have seemed preposterous. Similarly, very few people would have thought it possible that the top 500 supercomputers and the majority of websites would run on software produced in the same way.

The people who contribute to Wikipedia or Linux codes primarily want to create something useful for themselves, and for other people, not for the market or for short-term profit. the first wave of CBPP

(Commons-based peer production) included open-knowledge projects (code, culture, design), the second one is moving towards manufacturing. Imagine a prosthetic hand, an orthosis, a wheel hoe or even a house designed in the same way that the Wikipedia entries or the GNU/Linux code lines are written.

This is not a far-fetched utopian vision, but something that is happening as you read this. All knowledge and software related to these artifacts are shared globally as digital commons.

These are developed by the labor of often very passionate people from all over the world.

Moreover, those who have access to local manufacturing machines (from 3D printing and CNC machines to low-tech crafts and tools) can, ideally with the help of an expert, manufacture a customized hand, a satellite, a wheel hoe or a house.

These are the stories of the OpenBionics project, which produces designs for lightweight robotic and bionic devices; of the Libre Space Foundation in Greece, which produces small-scale satellites; of the L’Atelier Paysan collective in France, which builds agricultural machines; and of the WikiHouse, which ‘democratizes’ the construction of sustainable, resource-light dwellings.

Consider for a moment the role that the invention of the printing press played in transforming European society.

An increasing number of humans communicate in ways that were not technically possible before. This in turn makes massive self-organisation up to a global scale possible.

Yet these technologies can work both for emancipation and supervision, for revolution and suppression, it also allows for the creation of a new mode of production and new types of social relations outside the market-state nexus.

The whole technology paradigm creates several new possibilities, as various human groups try to utilize them. Different social forces invest in this potential and use it to their advantage. Technology is therefore a focus of social struggle, rather than a predetermined ‘given’ that creates just one possible future.

As social groups appropriate a particular technology for their own purposes, social, political and economic systems can change. What kind of change depends on who uses the tools most effectively.

The absolute horrors we expose ourselves to in the news today may be nothing more than the last angry gasp of a flawed obsolete system in it's death throes. As long as the forces of greed and vulture capitalism don't gain an upper hand.

Creating public rather than private value, commons-based scenarios follow the digital logic just as much as, and maybe better than, its classic-capitalist protagonists whether in Silicon Valley or elsewhere.

Perhaps it is best to think of these commons-based scenarios as early pilot projects, with a great radical change in our attitude towards production and economics a possibility just around the corner.

Are we seeing the beginnings of a world catching up with Morris's vision?

Maybe.

As recently as two decades ago, most people would have thought it absurd to countenance a free and open encyclopedia, produced by a community of dispersed enthusiasts primarily driven by other motives than profit-maximization, and the idea that this might displace the corporate-organised Encyclopedia Britannica and Microsoft Encarta would have seemed preposterous. Similarly, very few people would have thought it possible that the top 500 supercomputers and the majority of websites would run on software produced in the same way.

The people who contribute to Wikipedia or Linux codes primarily want to create something useful for themselves, and for other people, not for the market or for short-term profit. the first wave of CBPP

(Commons-based peer production) included open-knowledge projects (code, culture, design), the second one is moving towards manufacturing. Imagine a prosthetic hand, an orthosis, a wheel hoe or even a house designed in the same way that the Wikipedia entries or the GNU/Linux code lines are written.

This is not a far-fetched utopian vision, but something that is happening as you read this. All knowledge and software related to these artifacts are shared globally as digital commons.

These are developed by the labor of often very passionate people from all over the world.

Moreover, those who have access to local manufacturing machines (from 3D printing and CNC machines to low-tech crafts and tools) can, ideally with the help of an expert, manufacture a customized hand, a satellite, a wheel hoe or a house.

These are the stories of the OpenBionics project, which produces designs for lightweight robotic and bionic devices; of the Libre Space Foundation in Greece, which produces small-scale satellites; of the L’Atelier Paysan collective in France, which builds agricultural machines; and of the WikiHouse, which ‘democratizes’ the construction of sustainable, resource-light dwellings.

Consider for a moment the role that the invention of the printing press played in transforming European society.

An increasing number of humans communicate in ways that were not technically possible before. This in turn makes massive self-organisation up to a global scale possible.

Yet these technologies can work both for emancipation and supervision, for revolution and suppression, it also allows for the creation of a new mode of production and new types of social relations outside the market-state nexus.

The whole technology paradigm creates several new possibilities, as various human groups try to utilize them. Different social forces invest in this potential and use it to their advantage. Technology is therefore a focus of social struggle, rather than a predetermined ‘given’ that creates just one possible future.

As social groups appropriate a particular technology for their own purposes, social, political and economic systems can change. What kind of change depends on who uses the tools most effectively.

The absolute horrors we expose ourselves to in the news today may be nothing more than the last angry gasp of a flawed obsolete system in it's death throes. As long as the forces of greed and vulture capitalism don't gain an upper hand.

Creating public rather than private value, commons-based scenarios follow the digital logic just as much as, and maybe better than, its classic-capitalist protagonists whether in Silicon Valley or elsewhere.

Perhaps it is best to think of these commons-based scenarios as early pilot projects, with a great radical change in our attitude towards production and economics a possibility just around the corner.

The danger, were such a path to be fully co-opted by the current (very) dominant context, is obvious, and it must realistically be acknowledged. If you profit from an economic model on a large scale, if you draw your rents from it, why would you not fight for it, even when this is not good for anyone else? The counterculture is not only here, it is gaining ground, so far.

Morris envisioned a future in which humans would be free to create

and to ‘delight in the life of the world’. This is no longer far fetched.

Most menial labor that people are not fond of doing could be done by machines.

The maintenance of infrastructure can be shared.

People will be free to work at whatever task gives them pleasure.

It's a real possibility. And it's within grasp.

Comments

Post a Comment